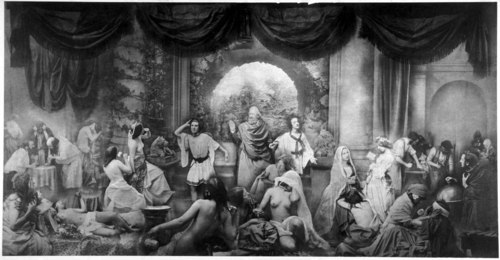

The Two ways of life, 1857, épreuve au charbon d’après épreuves papier

albuminé originale, 40,5×78 cm, Bradford, National Media Museum, Royal

Photograhpic Society Collection.

If we had to chose only one image to illustrate thebeginning of photography in the artistic world it would certainly bethis one.

Photography is used by numerous artists since its

apparition but is perceived as tool for inspiration more than as an

artistic realisation. Photography allows to represent an image very

similar to reality and can be used by the painter to create a

masterpiece.

Some artists find in photography a tool, like a

paintbrush, allowing to create an artistic work. The recognition of

this medium as a possible support for artistic expression will become

a struggle that continues today. Refused in art expositions,

photography is first presented to the public only as a result of a

technical progress.

With The two ways of life, O.G.

Rejlander proves through practice, that photography can be used

directly as a way of expressing the artist imagination. This work of

art proves that photography can be used to represent with great

precision the reality as well as the «imaginary».

Through this allegory, O.G. Rejlander depicts the

foils (frivolity, prostitution, gaming) and virtues (the man of

science, the devoted women, and the one reading) of society. It’s a

critic of idleness and a valorisation of expected behaviours in the

Victorian society.

This photographic « tableau »

questions the contemporary artists of O.G. Rejlander in many aspects

that we will mention below.

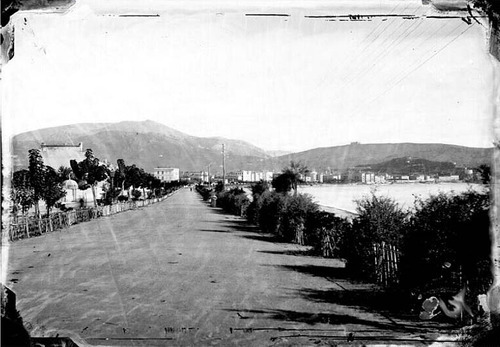

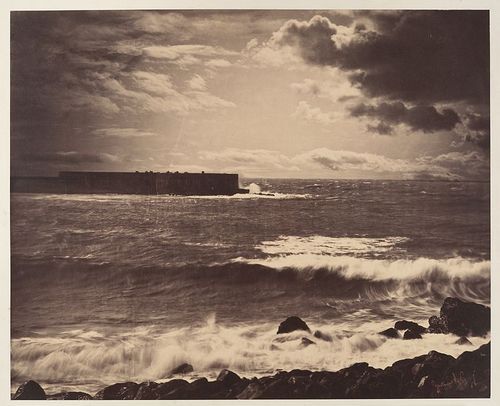

La

Grande Vague, Sète, photographie de Gustave Le Gray, 1857, Tirage sur

papier albuminé d’après deux négatifs sur verre au collodion, 357 x

419 mm, Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des

Estampes et de la photographie.

The technique used in this photography is questioned

by O.G. Rejlanders contemporaries. The reaction of some of them

proves that they didn’t understood that in order to realise this

masterpiece, the photograph didn’t gathered and displayed all the

characters (among which we can find naked women) at the same time. To

create The two ways of life,

O.G. Rejlander used 30 photographies and spent more than 6 weeks

taking and assembling every cliché shaping this composition.

The photograph uses

to its extreme the technique of assembling slides. But already before

him, other artists like Gustave Le Gray, used similar, but less

ambitious, compositions.

In The

great wave, Sète, Le Gray uses

this process in order to have an homogeneous exposition in the

photography. He takes two pictures, one with a posing time

sufficiently short to reproduce the clearest details of the sky and

the other with a longest one to capture the details of the darker see

and rocks. Le Gray will take an impotant amount of photographies

using this technique.

The choice of O.G. Rejlander of collage is justified

by several reasons. This technique solves the problem of sharpness in

different plans and allows a rich and complex composition as

presented in The two ways of life.

In order to consider the photographic medium as an

artistic one O.G. Rejlander doesn’t chose his subject randomly. The

two ways of life, original for

the technic used, contains the theme of the Athens school,

of Raphaël. We find the two main characters holding hands and a

cohort of busy or idle individuals.

The choice can be explained in two ways. The

intention of O.G. Rejlander is to represent both decay and the

industry of his city. This two behaviours are in contradiction as the

groups of individuals represented. The choice can also be explained

by the desire of presenting the photographic medium as an artistic

one. Showing that it is possible to create as complex and evocative

work as the italian painters of the Renaissance,

O.G. Rejlander manages to convince about the artistic potential of

photography.

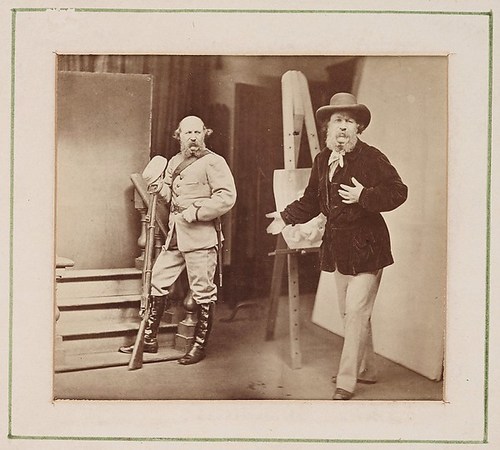

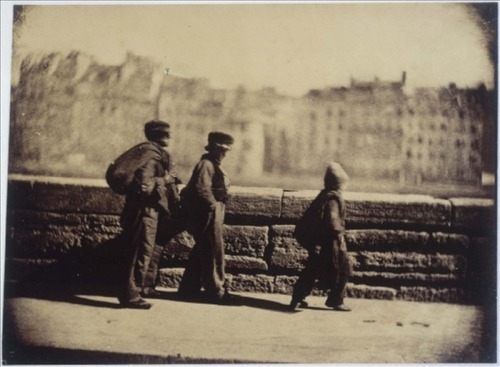

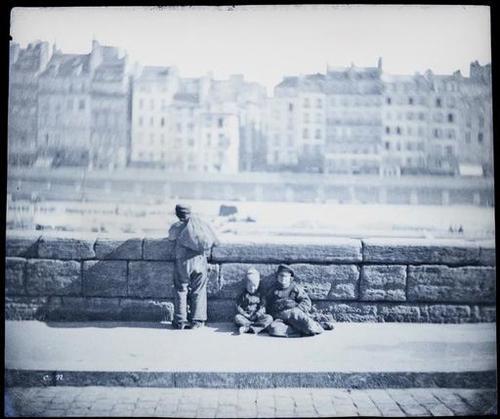

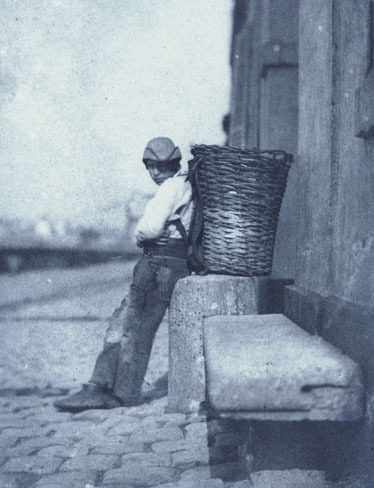

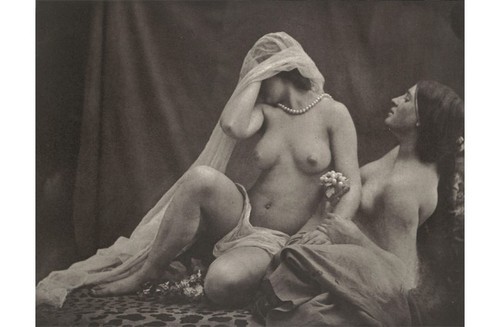

One of the photographies used for the realisation of “The two ways of life”

The Two Ways of Life also

questions the use of nudity in photography. If nudity in paintings is

admitted, nudity in photography causes scandal. Realism and detail of

photography reflects exactly the reality of the bodies. This realism

and detail shocked a segment of the victorian society in that time.

The controversy is soothed when Queen Victoria buys

for Prince Albert a copy of The two ways of life.

But it appears again when Scottish Society refuses to exhibit the

work in an exposition in Edinburgh.

Thomas Sutton, photographic editor of The News

and responsible of the exposition, justifies this reject by the

necessity to preserve the dignity of the women portrayed. In fact,

O.G. Rejlander affirms that the models are actresses and actors, when

other argue that they are prostitutes. Nevertheless, the fact that

the artist lied or not about this isn’t taken into account in Thomas

Sutton argumentation. It is the nudity and the carnal representation

that justifies the rejection of this work.

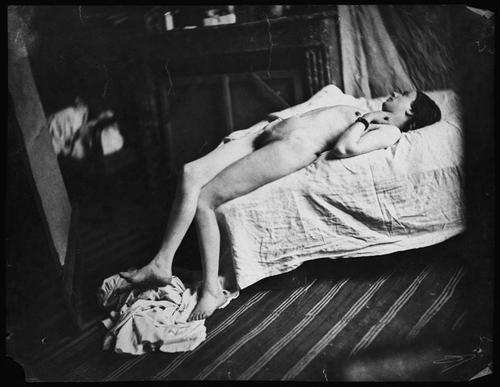

Furthermore, the argument about the social background

of the models, is not raised when it comes to painting. As a matter

of fact, it happens that painters ask photographers for nude

photographies as models for their paintings. Here are two examples :

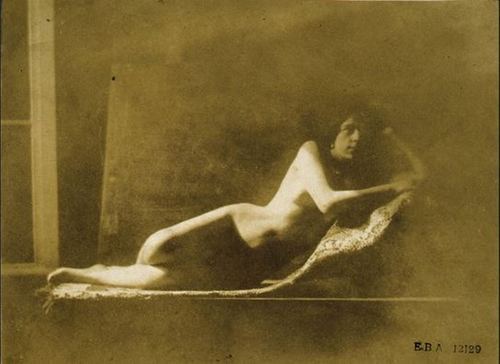

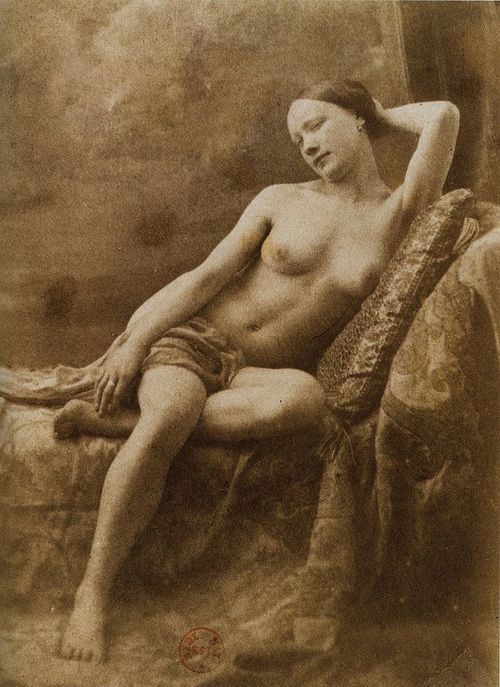

Nu

féminin assis sur un divan, la tête soutenue par un bras par Eugène

Durieu, papier salé verni d’après négatif papier, 14 x 9,5 cm,

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des Estampes et de la

Photographie.

Odalisque,1857, par Eugène Delacroix, huile sur panneau de bois, Collection privée.